There's no better way to get back into the blogging habit that just starting. I've intended to do this countless times and always got interrupted before I could finish. Now here we are, at the beginning of another new year and I'm long overdue for an update! I've tried to keep up with many of you as you traversed your busy year too, but I know I've missed some of your adventures. Why does life have to move along so quickly?

This blog post is longer than I usually write, but I'll try to briefly recap what I've been up to, with some more detailed blog posts later.

January brought a bathroom remodel that was a year later in coming than we'd planned. We only have one full bath in this house, and it had been 25 years since the last update, so this was kind of a big deal.

This gave me great satisfaction, because it shows you don't have to “be someone” to get things done. With the sale of each monarch organizational plate,

Monarch Wings Across Ohio will receive $15 for monarch research. As long as 25 plates are sold each year, they will keep it available to anyone who has a licensed vehicle in the state of Ohio.

|

Monarchs cling to oyamel fir trees in the Sierra Chincua monarch reserve

in the Transvolcanic mountains of Central Mexico. |

The end of

February found Romie and me heading south to Mexico to see the monarchs in their overwintering grounds.

Beth and Ernie Stetenfeld from Wisconsin joined us for the six-day trip, and I can't say in a brief paragraph what a wonderful experience it was to fulfill this bucket list item. So there will definitely be a few more posts about it.

March ushered in a much anticipated spring and all of a sudden, it was

April. This was a roller coaster of an emotional month, as my second book,

THE MONARCH: Saving Our Most-Loved Butterfly, was released. On Earth Day, April 22

nd. The Paulding County Carnegie Library hosted a book release party and the event was very successful and a lot of fun.

Later that same day, my 102-year-old grandma passed away. We knew it was coming, and she lived a wonderfully long and full life, but it doesn't make it any easier. In fact, it might be harder, because when you've had a grandma like her for nearly 60 years, you really can't imagine your life without her. But we do have hundreds and hundreds of memories to cherish.

|

This photo of my grandma and me was taken on Christmas Eve 2016, two

days before her 102nd birthday. It's the last photo I have with her. |

When I was writing my book, I consulted with

Dr. Lincoln Brower, one of the world's foremost authorities on monarchs. He's in his 80s now and is a research professor at Sweet Briar College in Virginia. I wanted to meet him and personally give him a copy of my book, so I asked if I could do so. He graciously invited me to his home so Romie, my mom, and I planned a trip for May. We spent the afternoon with him and then we all went to dinner. Meeting him was one of the highlights of my year.

|

I enjoyed my conversation with Dr. Lincoln Brower when I visited him in

his Virginia home in May. |

On this same trip, we stopped in Pittsburgh to visit my publisher's offices –

St. Lynn's Press. We learned that the office space was previously held by a company that my husband's employer does business with on a regular basis. It was a “six degrees of separation” moment!

|

Me, with my St. Lynn's Press #TeamMonarch: Holly Rosborough, Chloe Wertz,

and Paul Kelly. My editor, Cathy Dees, was away, in California. |

|

| Phipps Conservatory in Pittsburgh |

|

| Downtown Pittsburgh at night, as seen from the West End Overlook |

We then headed a bit south, where we visited the

Flight 93 Memorial. Mom and I had been there twice before, but it was Romie's first time. It's a moving experience, no matter how often you see it.

Continuing on south, we headed to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, for that visit with Dr. Brower. After overnighting at Sweet Briar College's

Elston Inn, we kept going south.

|

| My grandma was born here in 1914. Called Ravenwood, it was built in 1849. |

Because we were close enough to Crewe, Virginia, birthplace of my grandma that had just passed away, we wanted to try to find the house where she was born. We knew it was still standing. After a really interesting series of conversations with locals, we found it. I wish we would have been able to share the experience with her.

|

Jacqui Knight, from New Zealand, was an absolute delight, and she came

to the Paulding County Master Gardeners plant sale before continuing on her

journey. I was selling and signing my books at the sale. |

Also in May, I was thrilled to have a visit from Jacqui Knight, Trustee with

Monarch Butterfly New Zealand Trust. Jacqui lives in Auckland and was in the U.S. on an ambassador trip, visiting key locations in our country for gathering information about the monarch. She visited Monarch Watch at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas, where she met MW founder, Dr. Chip Taylor. She also stayed with Dr. Brower in Virginia, and was working her way back west when she spent a night with us.

|

| Just a mile from us, power lines were knocked flat by straight line winds. |

We showed her some good old

Paulding County straight line winds, complete with a power outage! Since we had no power, we drove to Van Wert for supper. We didn't regain our power until late that night, but since you don't need electricity to talk, Jacqui and I had some good conversation about the monarch we both love so much. New Zealand has its own small population of monarchs.

|

The U.S. Botanic Garden is situated on the National Mall, near The Capital.

See the dome of The Capital just left of center? |

June brought the annual Garden Bloggers Fling, this time held in the Washington, D.C. area. I'll have more later on the gardens we saw, but one of the highlights of the Fling is getting to be with garden blogger friends that we may only get to see once a year, as well as meeting some for the first time.

|

| This is just part of the spectacular rock gardens at Chris Hansen's home. |

We weren't home very long when Mom and I took off again, this time to Holland, MI, where we visited Chris Hansen, breeder of the popular

SunSparkler® and

Chick Charms® sedums. His gardens at his beautiful home are captivatingly designed and I wanted to spend oodles of time looking at the hundreds of varieties of rock garden plants he has there.

|

Susan Martin's property is almost entirely in shade, so she has surrounded

her home with a carpet of texture and a kaleidoscope of greens. |

We spent a few days at Chris's home, but we also got to visit one of our favorite garden centers,

Garden Crossings (why can't all garden centers be like this?), Chris's

Garden Solutions business site, the

Walters Gardens display gardens, and we also got to have dinner with

Susan Martin, as well as visiting her lovely woodland garden.

July always means a trip to Columbus to attend the

Cultivate trade show, where we get to see all kinds of new plants and garden products, as well as talk with industry people. We're fortunate that this is held in our backyard and is an easy trip to our state's capital. Being a member of

GWA (Garden Writers Association) has its perks when it comes to this show, too. (Free admission!)

|

We saw a myriad of garden ideas in the private gardens of Buffalo that we

toured at the GWA Expo and Symposium. |

The busy summer wasn't over yet. The annual GWA Expo and Symposium was held in

August in Buffalo. Mom and I drove up for it and not only did we get to see some of the fabulous gardens that are part of the famous

Garden Walk Buffalo every summer, we took a day and went over the border into Canada, to see Niagara Falls and some gardens there. I'll share more of that in another post, too.

|

| Thanks to our Canadian neighbors for the red, white, and blue display! |

Later in the month, Romie and I drove to Nashville to experience the total solar eclipse with our friend,

Barbara Wise. I love spending time with Barbara and this was made extra special because of the eclipse. If you've never experienced seeing it in totality, you really must put that on your bucket list. It's nothing like seeing a partial eclipse. Trust me.

August begins the tagging season for migrating monarchs, and this year, we raised and tagged more than 100 monarchs and sent them on their way to Mexico. It was a great year, and all signs point to the numbers in Mexico being up when they do the count down there for the winter.

Speaking of monarchs, at the end of August, we were host to Butterbiker

Sara Dykman, who was on her way back to Mexico and was passing through our area. I spearheaded arranging to have her speak in Ft. Wayne at the University of St. Francis as well as our local elementary school students.

|

Sara Dykman, a biologist from Kansas City, as she's leaving a two-night

stay at Our Little Are. |

Sara recently completed a 10,201-mile round trip from Central Mexico to Canada and back again, following the monarch migration, all on her bicycle, spreading monarch awareness all along the way. She's the only person to have done this.

|

| The time together is never long enough. 💕 |

We were excited for September to arrive, because our exchange student from Ecuador, who lived with us in 1993-94, Karina, came for a visit, with her husband and two little boys. It was the first time our daughters had seen her since she last visited in 1999. Needless to say, we had an absolute wonderful time and it was fabulous to have her sleeping under our roof again.

|

| Photo courtesy of Jean Persely. |

I had a few speaking engagements this fall, including one at the Monarch Festival in Ft. Wayne, IN. Romie and I also traveled to Midland, MI, in October, where I spoke to a wonderful group of Master Gardeners and others from the community.

|

| Photo courtesy of Carolyn Turner |

Healthwise, the fall wasn't great, as I battled strep twice and bronchitis, but things slow down during that time anyway, with the exception of the holidays. By the middle of November, I was able to get together with several of my fellow dental hygiene classmates (IPFW – Class of 1977), some of whom I hadn't seen for nearly 40 years.

|

It's amazing how you can be apart for so long, but once you're back

together again, it's almost as if no time has passed at all. (Almost.) |

That's pretty much it, along with some book signings and a lot of interviews for podcasts, radio, and TV shows. (More about those later.) It was certainly a busy year, but also a fun one and 2018 is looking pretty good, too.

My next speaking engagement is the regional

Perennial Plant Association regional meeting in Chicago at

Morton Arboretum on February 3. I'll be sharing the program schedule with

Doug Tallamy, author of the bestselling

Bringing Nature Home. Yep, I'm name-dropping and I'm a tad bit nervous about the whole thing, but I'm also looking forward to meeting him and hearing him speak.

Now that you're caught up, I'll do my best to share some details of these fun activities in future posts. And I promise not to go AWOL for so long either. If you're a long-time reader, thanks for hanging in there with me, and if you're new to Our Little Acre, welcome! I encourage you to look through the archives for gardening ideas as well as my ongoing adventures with monarchs.

And I've got some exciting news on that monarch front! Stay tuned! 🦋

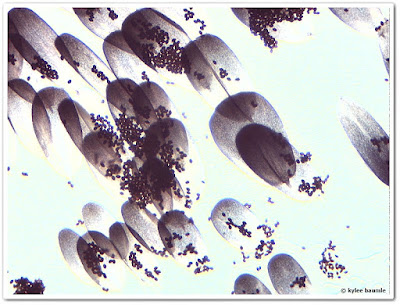

"Bejeweled"

"Bejeweled"