The migration of the monarch butterfly is a well-known natural annual occurrence in North America. In the fall, hundreds of thousands of monarchs wing their way from Canada to Mexico to escape the cold winters of the north.

But they often make a relatively long journey even before they embark on their winged flights.

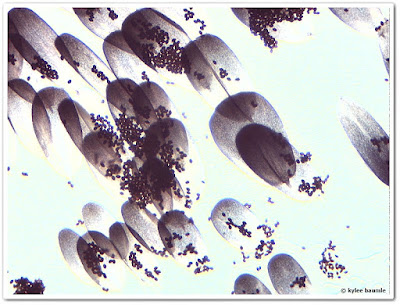

The monarch life cycle is this: an egg is laid, then 3-5 days later, a tiny caterpillar eats its way out of the egg. For the next two weeks, it eats copious amounts of milkweed, sheds it skin five times as it grows, until it eventually pupates, taking on the familiar green chrysalis form, dotted with golden jewel-like spots. After spending roughly two weeks in chrysalis, it emerges as an adult butterfly.

When it's time to become that chrysalis, the fat caterpillar most often wanders from the milkweed it's been eating, to find a safe place to hang out for a couple of weeks. If you've read my book - THE MONARCH: Saving Our Most-Loved Butterfly - or others, you've read that they can crawl up to 30 feet or more away from their food source to make their chrysalis.

Several years ago in late winter, I was cleaning out the bluebird box on our shagbark hickory tree, when I noticed an empty chrysalis case hanging from the bottom of the box. It looked like the eclosure was successful from what I could tell and it made me smile. And then I realized just how far it was from the closest milkweed.

I stepped it off and it was 70 feet from the nearest milkweed. Such a long walk for a caterpillar!

Last weekend, daughter Kara and I were at Point Pelee, Ontario, Canada, hoping to see hoards of monarchs at the tip (we did not). We made the trip mostly to hear a presentation by Dr. Anurag Agrawal, Professor of Environmental Studies at Cornell University, and author of Monarchs and Milkweed.

While we were there, I got a text from my husband, with a photo attached. It was a picture of an empty monarch chrysalis, attached to a headstone down at the cemetery near our house.

It's not the easiest thing in the world to find a chrysalis in the wild, occupied or not, because they're usually well-hidden, especially when they're in the garden. It was a great find.

When I got home, I wanted to see it for myself, so we walked to the cemetery and he showed me. There it was, attached to one arm of a stone cross carved into the headstone. He had been looking at something else on the stone and then noticed the chrysalis.

|

It was likely a recent eclosure, because the area below the chrysalis was still stained by the reddish-brown meconium that the butterfly expresses shortly after it ecloses. It was a unique location, to be sure, but it was not in the part of the cemetery where I'd assumed it would be.

There is some milkweed on the south border of the cemetery, where the land falls away into a field. It would be more expected to find a chrysalis there. But this one was far from that, out in the open. Where was the milkweed?

We looked around and Romie spotted it growing between two tall shrubs, but those shrubs were not close. I stepped it off and it was 85 feet from the headstone. There were other headstones that were closer that had equally appropriate niches for chrysalis-hanging.

Oh, what I would give to be inside the head of that caterpillar as it inched its way to its place of pupation. 1,020 inches, give or take, through the grass and 22 more up the stone. Eighty-five feet for a caterpillar is the rough equivalent of 1.2 miles for a human.

|

| 85 FEET!! |

"Bejeweled"

"Bejeweled"